Bethesda Memories

President Franklin Roosevelt Designs the new Naval Hospital in Bethesda

In December 1937, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt sketched out on White House stationery his vision for a new naval hospital to be built in the Washington area. He based his design on the new Nebraska State Capitol building in Lincoln (below) that had impressed him when he dedicated it during his 1936 reelection campaign. Roosevelt called it a “wonderful structure” that Americans “ought to come here and see.”

Roosevelt, one of two presidents to design buildings (the other was Thomas Jefferson), had overseen construction of buildings in his hometown of Hyde Park, New York, and various government structures in Washington D.C.

Roosevelt, one of two presidents to design buildings (the other was Thomas Jefferson), had overseen construction of buildings in his hometown of Hyde Park, New York, and various government structures in Washington D.C.

On a automobile ride into Maryland in July 1938, Roosevelt found the perfect location for the hospital, opposite the site of the future National Institute of Health in Bethesda. “We will build it here,” he said tapping the ground with his cane. Four years later in 1942, FDR dedicated the National Naval Medical Center.

See “A Tower in Nebraska: How FDR Found Inspiration for the Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland” by Raymond P. Schmidt (2009)

Bethesda Memories

How NIH’s Main Campus Came to Be in Bethesda

From the mid-1930s to the early 1940s, Luke Ingalls Wilson, a successful businessman and long-time friend of President Franklin Roosevelt, along with his wife Helen and their son Luke, donated 92 acres of their estate along Rockville Pike to the federal government for a campus dedicated to medical research.

Roosevelt dedicated the buildings and the grounds of the National Institute of Health on October 31, 1940.

In the above photo, Helen Wilson is sitting on a rock wall by the lane leading to her estate from Rockville Pike about 1934.

For more of the story, see “How NIH’s Main Campus Came to Be in Bethesda” by Michele Lyons and D.S. Wilson mon the NIH website.

Bethesda Memories

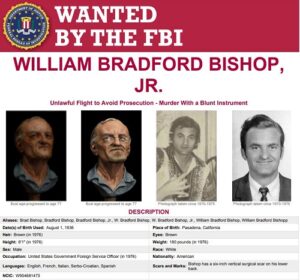

William Bradford Bishop, Jr., Commits Most Heinous Murders in Bethesda History

On March 1, 1976, 39-year old U.S. State Department Foreign Service officer William Bradford Bishop Jr., after learning he would not receive the promotion he wanted, left work to withdraw several hundred dollars from his bank. He then drove first to Montgomery Mall, where he bought a sledgehammer, gas can, shovel and pitchfork and then to a gas station where he filled the can and his station wagon with gas.

Bishop returned to his home on Lilly Stone Drive in the Carderock neighborhood near Seven Locks Road in Bethesda and that evening killed his wife, then his mother, and finally his three sons ages 5, 10 and 14. He loaded their bodies into his station wagon and drove 275 miles to a wooded swamp in North Carolina where he dug a shallow grave and set the bodies on fire. Two and a half weeks later, his car was found abandoned at an isolated campground in Tennessee at the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

A decades-long international manhunt followed, but Bishop vanished and was never caught. The U.S. Marshalls Service believe there were three brief credible sightings of Bishop in Europe in 1978, 1979, and 1994 by people who had known him. If still alive, he would be 87 in 2023.

More at “The Man Who Got Away” by Eugene L. Meyer.

Bethesda Memories

How NIH’s Main Campus Came to Be in Bethesda

From the mid-1930s to the early 1940s, Luke Ingalls Wilson, a successful businessman and long-time friend of President Franklin Roosevelt, along with his wife Helen and their son Luke, donated 92 acres of their estate along Rockville Pike to the federal government for a campus dedicated to medical research.

Roosevelt dedicated the buildings and the grounds of the National Institute of Health on October 31, 1940.

In the above photo, Helen Wilson is sitting on a rock wall by the lane leading to her estate from Rockville Pike about 1934.

For more of the story, see “How NIH’s Main Campus Came to Be in Bethesda” by Michele Lyons and D.S. Wilson mon the NIH website.

Bethesda Memories

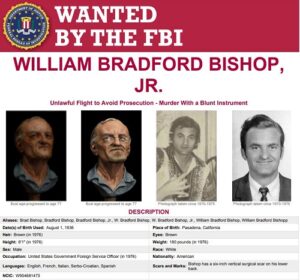

William Bradford Bishop, Jr., Commits Most Heinous Murders in Bethesda History

On March 1, 1976, 39-year old U.S. State Department Foreign Service officer William Bradford Bishop Jr., after learning he would not receive the promotion he wanted, left work to withdraw several hundred dollars from his bank. He then drove first to Montgomery Mall, where he bought a sledgehammer, gas can, shovel and pitchfork and then to a gas station where he filled the can and his station wagon with gas.

Bishop returned to his home on Lilly Stone Drive in the Carderock neighborhood near Seven Locks Road in Bethesda and that evening killed his wife, then his mother, and finally his three sons ages 5, 10 and 14. He loaded their bodies into his station wagon and drove 275 miles to a wooded swamp in North Carolina where he dug a shallow grave and set the bodies on fire. Two and a half weeks later, his car was found abandoned at an isolated campground in Tennessee at the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

A decades-long international manhunt followed, but Bishop vanished and was never caught. The U.S. Marshalls Service believe there were three brief credible sightings of Bishop in Europe in 1978, 1979, and 1994 by people who had known him. If still alive, he would be 87 in 2023.

More at “The Man Who Got Away” by Eugene L. Meyer.

Bethesda Memories

Harry Truman dedicates Madonna statue in 1929

Future President Harry Truman dedicated the 12th and final Madonna of the Trail statue in Bethesda in 1929. The statues, organized by the Daughters of the American Revolution, were erected to mark the network of old trails across the country and honor pioneer women. Truman, 45, a Kansas City, Missouri, county commissioner (called a “Judge” there), was President of The National Old Trails Road Association.

“It was the grand old pioneer mother who made the settlement of the original thirteen colonies possible,” he declared at the dedication before a crowd of 5,000 on April 19, 1929. “She made this country what it is by being the hearty mother she was and producing sons and daughters to make it great.”

Locations of the 12 statues at madonnatrailbethesda.org.

Read more about Bethesda’s Madonna of the Trail here.

See previous Bethesda Memories here.